Ethical Issues in Qualitative Interviews

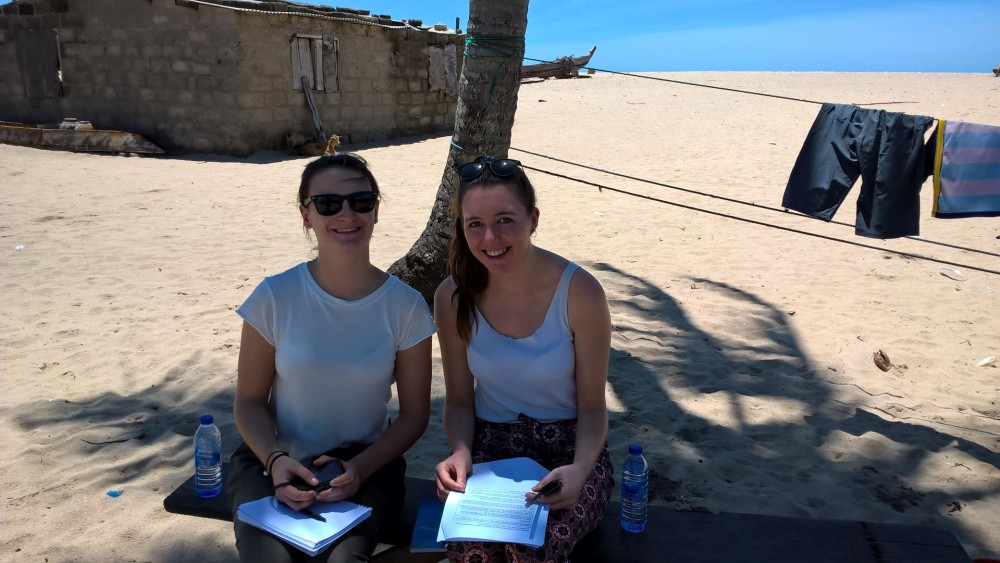

Qualitative interviews are a commonly used research method to learn about different people’s experiences, knowledge, ideas and motivation, behaviour and values, the list could continue on further (Schostak, 2006). Ethics play a crucial role in how interviews are conducted and the reliability and validity of the results. If research is not ethical it would be disregarded by academics and rendered useless. The main three ethical issues spoken about throughout are informed consent, confidentiality and privacy and then finally intrusiveness and coercion. These issues will be linked to real life qualitative interviews on costal erosion and climate change undertaken for practice and experience in the Ada Foah delta region in Ghana. The purpose of these interviews was to gain knowledge of qualitative date collection and to learn how the different processes work.

Informed consent was established in 1949, and then in 1974 stricter regulations were put into place after various unethical studies which did not fully inform participants on the aims and plan of the study therefore felt that taking part was a requirement (Bryman, 2012). Participants who took part in the interviews in Ada Foah were given an approved participant information sheet which explained the process of the interview and why it was taking place. However, a major obstacle in the effectiveness of this was the participant’s limited English proficiency (LEP), this means that many only had a basic level of English ability (Escobedo, 2007). These language barriers posed the question of whether informed consent had been successfully provided. One of these questions was whether participants understood their rights that they do not have to answer questions and can withdraw at any time, they may have continued with the interview even if they felt uncomfortable and unhappy (Escobedo, 2007). A further issue is that participants may have felt a level of expectation or that something good may come out of the interviews, for example, better and more improved sea defences will be built. Participants may have been unaware or did not understand it was only a training exercise. Therefore, the idea of false expectations may arise, which would lead to disappointment and may prevent further research being able to be conducted in that area. Informed consent could be improved in many ways such as have a translator present or translating the informed consent sheet into the local language. Talking through the participant sheet may have helped their understanding and using less complex language (Escobedo, 2007).

Another ethical issue present was the lack of privacy and confidentiality involved. These are put into place to ensure participants are unidentifiable to reduce the risks of harm, and also to encourage openness (Miller, 2012). The interviews that took place were open and outdoors, this meant that participants could easily be identified by people who live in the village. People would regularly walk passed and distract the interview. This may have caused participants to feel uncomfortable and not open up as much as they could have. It also could put the participants are risk of harm and stigma as other members are the village may not have felt comfortable about them taking part. To rectify this the interviews could have taken place in more private places, such as a building or inside someone’s home. However, this was probably not a practical solution as it could cause the interviewer to feel uncomfortable.

The final ethical issue to mention is intrusiveness and coercion. Intrusion entails interfering with the participants time and space, this may have been more dominate in the practice interviews as a group of highly educated white people have travelled to small costal town in Ada Foah, therefore they may have felt invaded with us being there (Miller, 2012). It could have led to negative feelings towards the interviewers as they did not fully understand the purpose of the research and practice. This links to the issue of coercion as participants interviewed may have not wanted to take part in the interviews, however the gatekeeper and recruiter may have forced participants to be involved in the interviewing. As they spoke the local language, it could not be made clear if this was the case but on a few occasions participants behaviour suggested ideas they were not happy to be involved. The prevention of this may be difficult to achieve because of the language barriers, trust has to be put in the gatekeeper or fellow researcher that they have approached recruitment in an ethical way.

Overall, the interviews had many issues and there were several areas which could be changed to improve on interviews in the future. Ethical issues effect the quality of the study and the results achieved, therefore it is crucial to follow ethical guidelines set out. The issues involved did effect the interviews and there execution because they prevented the interviews from flowing smoothly and effectively. However, many of these issues were hard to prevent due to many factors, such as lack of knowledge of the area and people.

Charlotte Owen

References

Bryman, A. (2012). Social Research Methods. 4th Edition. Oxford University Press. Oxford.

Escobedo, C., Guemero, J., Lujan, G., Ramirez, A. and Serrano, D. (2007). Ethical Issues with Informed Consent. Bio-Ethics. 1.

Lapan, S.D., Quartaroli, M.L.T. and Riemer, F.J. (2012). Qualitative Research: An Introduction to Methods and Designs. Wiley. Chichester.

Miller, T., Birch, M., Mauthner, M. and Jessop, J. (2012). Ethics in Qualitative Research. 2nd Edition. SAGE. London.

Schostak, J. (2006). Interviewing and Representation in Qualitative Research. 1st Edition. McGraw-Hill. Maidenhead.