The relationship built during an interview can often be a major influential aspect of gaining in-depth, truthful answers for a demographic project. Being one-on-one with a stranger, talking about a pre-determined subject can be quite daunting; particularly if other restrictive issues are involved, such as language barriers. Building rapport is more likely to influence the success of a qualitative interview rather than surveys for example, as interviewing has a greater need for dynamic and descriptive material, therefore the interviewee has to feel open to express their opinion in detail. This technique was very effective during our interviews in the Volta delta in Ghana; not only showing us the relationship between rapport and the responses, but also the issues that can arise when trying to create a rapport.

Before an interview commences, it is beneficial for the interviewer to take some time to introduce themselves and the project to the participant, as well as creating small talk to relieve any nerves before getting into the questions. This allows them to feel more comfortable in this strange environment, so respondents are more likely to provide more illustrative answers which helps to perform in-depth analysis of the results and draw reliable conclusions (Randall and Koppenhaver, 2004).

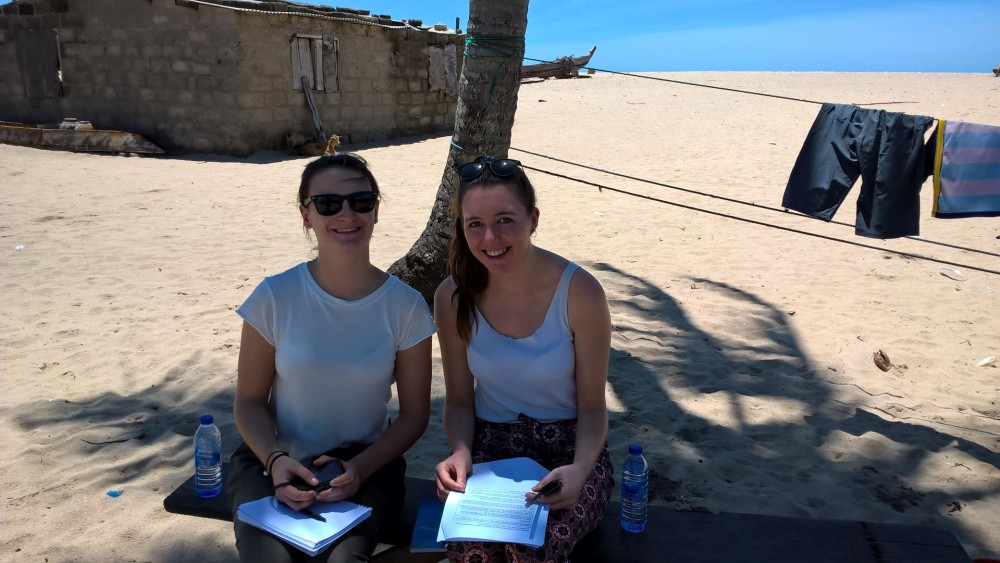

Rapport was significant to the interviews we conducted in Ghana as it was important for us to sympathise with these respondents as the research topic involved their home and work life. From the interviewer’s point of view, building a relationship with them allowed us to become more involved in the conversation; not just focussed on getting an answer, but developing their opinion to gain depth in the topic. It seemed that as we became more interested in what they were saying, they were more willing to converse.

During the interviews we conducted in Ghana, we found that rapport was hard to build initially. Firstly, we had never spoken to these people before so relating to them was difficult – in the beginning it felt quite false, especially as we were nervous ourselves. However, showing confidence during an interview reflects professionalism and ability, which helps the respondent to feel comforted that you are in control and know what you are doing (Legard et al, 2003). As the interview developed, we gained confidence and we able to adapt questions to react to the respondent’s answer.

A second issue we found with building rapport was the language barrier; as we were not using translators, there was some difficulty in helping the respondent to understand what we were saying. This was evident when comparing the first interview we conducted to the second; the first respondent understood English better than the second, so we were able to build a better relationship with him and ask more in-depth questions. The second seemed very nervous about answering questions, which we found difficult to amend as we were unable to comfort her. This meant the interview was very stiff and unadaptable, so we were not able to gain as much depth in her answers. As we couldn’t relax her through small talk, we tried different methods to build rapport such as eye contact, smiling and hand gestures to help her understand.

The third main issue we came across was time restraints and the trade-off between taking the time to introduce them to the project, and taking their personal time away – Gubrium & Holstein (2001) explain how rapport is not often “quickly achieved”, but may be a dependent factor on a successful interview. As the consent form we gave them stated we would not use more than 45 minutes of their time, we were wary of keeping them too long and taking advantage of their participation. In this way, we had little extra time to be able to talk informally with them and build a relationship – if we had more time, it is possible that they would have told us more personal experiences to do with the project as they confided in us more.

Building rapport is important for all interview situations, especially if the subject is sensitive to the respondent or they seem agitated by the questions. We found one of our greatest obstacles was the language barrier which is going to be a natural factor when conducting interviews in remote foreign locations. Coming up with solutions for problems like this enables the interviewer to feel more experienced and confident for next time – one thing we found is that if you (the interviewer) are relaxed, your respondent is more likely to reflect the same relaxed feeling and the interview will go a lot smoother!

Alice Sanders

References

Legard, R., Keegan, J., Ward, K. ‘In-depth Interviews’ IN: Richie, J., Lewis, J. (2003), Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. London: Sage.

Randall, S., Koppenhaver, T. (2004), ‘Qualitative data in demography: The sound of silence and other problems’, Demographic Research. 11(3), p57-94. Rostock: Max Planck Institute.

Gubrium, J., Holstein, J. (2001), Handbook of Interview Research: Context and Method. London: Sage.